“If Men were angels, no government would be necessary” – James Madison famously said. However, that’s not what we are dealing with in reality: political power and authority is exercised by fallible people over fallible people – with no angels at either end. Our research at the MCC Center for Constitutional Politics examines how this political authority is created and, at the same time, constrained by constitutions adopted by imperfect people. The research projects of the Center seek to answer the question of how political actors and judges – who are the guardians of the constitution – bring the constitution to life, how the most fundamental rules of a political community are adopted, followed (or disregarded), enforced or even reshaped. In the 21st century, the boundaries of political communities are increasingly called into question and being redefined. Thus, our work covers the examination of questions of national sovereignty, European and global constitutionalism. The Center for Constitutional Politics offers MCC students a range of debate-style courses, allowing them to engage in guided discussion over the questions of political and constitutional theory that affect their everyday lives.

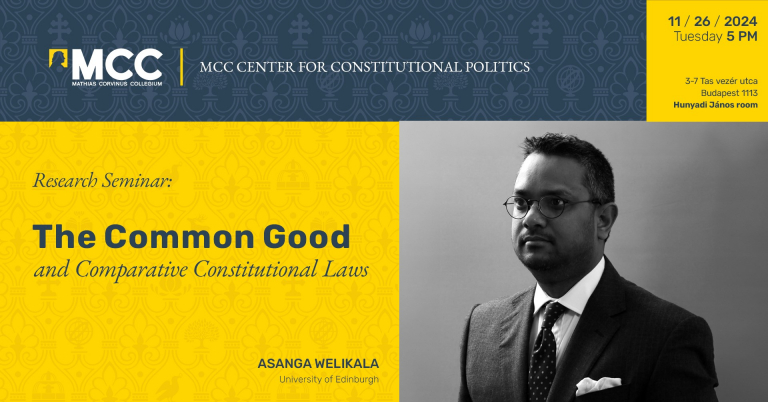

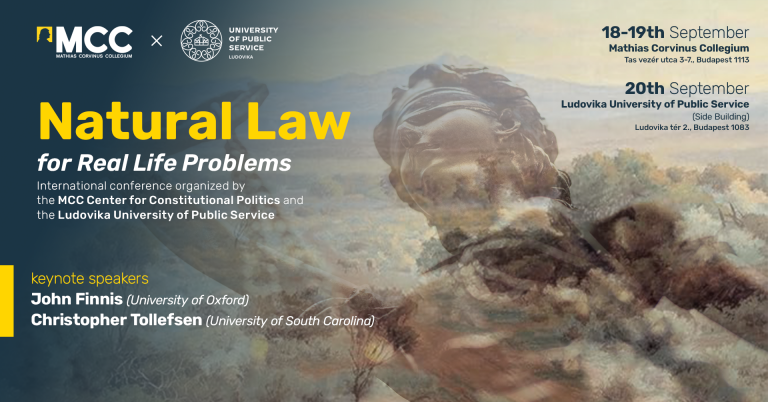

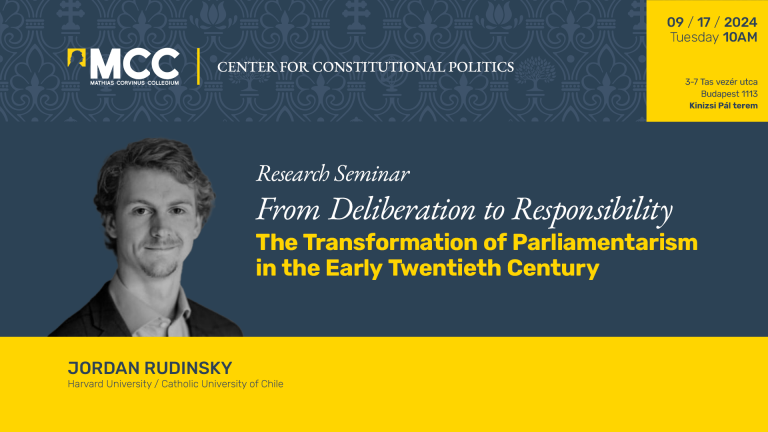

The MCC Center for Constitutional Politics hosts several conferences and guest lectures. Invited speakers include:

Click here for the Hungarian version of this site:

Political philosophy in everyday life: utilitarianism and libertarianism

Political decisions often present decision-makers with serious dilemmas. Beyond political gain, they must also answer difficult questions such as: Why is it compulsory to wear a seat belt? Is taxation really the same as forced labour? Should the rich pay proportionally more tax? Why should property rights be sacred? Why is compulsory military service good/bad? Should voluntary surrogacy really be banned? During the course, students will debate the most fundamental questions of political philosophy, using practical examples to illustrate the arguments for and against.Political philosophy in everyday life: beyond utilitarianism and libertarianism

The course will not revisit the topics covered in the course Political Philosophy in Everyday Life (utilitarianism, libertarianism), but will introduce students to the political dilemmas of equity and virtue. In addition to political utilitarianism, policy makers have to answer difficult questions such as: should the human dignity of murderers be respected? Why can't a man born outside the US be President of the US? Should those born into poverty be compensated somehow? Does the talent born with us create social injustice? Should we require Hooters to hire male wait staff? Are we really not allowed to lie under any circumstances? Is there really no better principle of social organization than meritocracy? Is positive discrimination necessary? Why should one be loyal to one's country? What is patriotism: virtue or harmful prejudice? Does the common good exist? During the course, students will debate the most fundamental questions of political philosophy, using practical examples to illustrate the arguments for and against.European Union and the Nation States

The course aims to develop students' argumentation skills and debating culture by engaging with the controversial issues of European integration. It aims to shed light on how current domestic and foreign policy debates on the future of the European Union and nation states can be interpreted in a broader perspective, which theoretical arguments can be used to support contradictory positions and which practical examples can be given by the proponents of the different positions. The course will function like a classic debate forum in which the lecturer will play both the role of moderator and devil's advocate.Constitutional engineering: let’s design the perfect political system!

Which is the best political system? The course attempts to answer this question - with the active participation of the students. The aim of the course is to enable students to argue for (and against) their preferred combination and type of political institutions. To this end, students will be asked to design an ideal political system within an imaginary constitutional process, expressing their views on how the system should be changed and justice established, or even on the nature of the constitutional process. In response to the arguments of others, students formulate their views on the political system they think is best.Smokey cigar lounges – connection between politics and media

The course aims to familiarise students with the situation, general characteristics and challenges of today's regional media market from an international perspective. In this context, the relationship between media and politics will be examined: How do these two actors influence each other, what are their responsibilities towards society? We will examine the role of the media in politics, the power of PR and the power of lobbyists. We will look at the instruments of politics in the media market, the power of campaigns and their relationship to the fourth branch of power.Public law and globalisation - constitutionalism without borders?

Can we speak of a constitution or constitutionalism without nation states? Can the concept of law, especially constitutional law, be separated from state sovereignty? Most fields of law are trying to find solutions to the challenges of economic and social globalisation, and constitutional law is no exception. Although the notion of constitutionalism is traditionally associated with nation states, the question of European and global constitutionalism is increasingly being raised as the boundaries of political communities seem to be blurring. The aim of this course is to illustrate the interaction between globalisation and public law: How does globalisation affect state constitutional systems and how can law be an instrument of globalisation?Ideologies and their symbols: 20th century totalitarianism and its symbol systems

Related news

How to Elect Judges? Judicial Appointments in Eastern Europe and Latin America