Reading time: 9 minutes

The issue of climate and environmental protection in the United States is an even more polarised political issue than in Europe. Republicans often refer to the Democrats as climate alarmists who are destroying the economy, while the latter often see the former as uninformed climate deniers. Moreover, this antagonism does not only permeate campaign communications, but also appears at the highest level of the hierarchy, i.e. at the presidential and presidential candidate level.

The Climate Policy Institute's analysis looks at the climate and environmental policies of Barack Obama's tenure, Donald Trump's presidency and the current Joe Biden administration to show how the world's leading economy has moved beyond simplistic policy communications. This analysis also provides a more informed forecast of the country's climate policy future in the event of a Harris or Trump victory.

The big picture

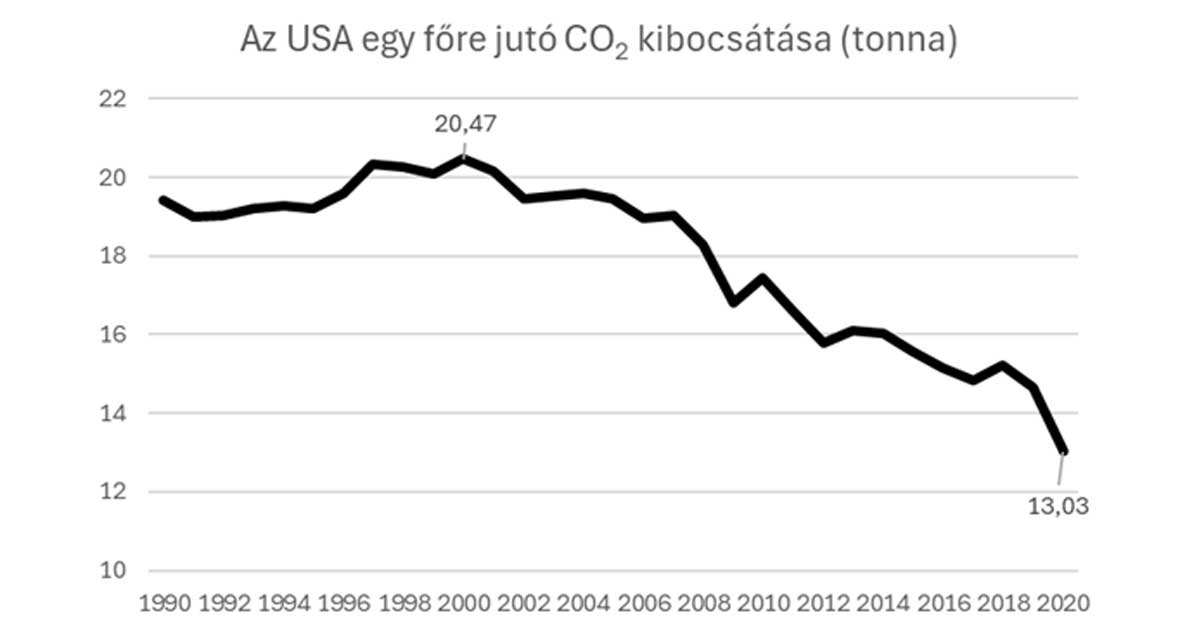

It is a good indication of the broad trends in US climate policy, regardless of administration, to look at per capita carbon emissions over a longer time horizon.

Per capita emissions peaked in 2000 at roughly 20.5 tonnes. The last figure in the graph, 2020, is deceptive, as emissions have fallen significantly worldwide in the early years of COVID due to drastic lifestyle changes. However, even between 2000 and 2019, there was still a significant drop in emissions per capita, down by around 28%.

The graph also shows that, although there are small peaks and valleys along the line, the fundamental goal of the presidents of the 21st century was clearly to reduce emissions, and this was met with social will. This reduction ambition can therefore be seen as an American national minimum, but a more nuanced picture of the details of the fight against climate change can be obtained by looking at the policies and results from presidency to presidency.

Barack Obama

The fight against climate change has traditionally been a Democratic issue in the US, at least it was in the early 2010s, and has featured prominently in Obama's communications. Beyond communication, however, it is mainly the second Obama cycle that has delivered significant results. As can be seen from the chart above, per capita carbon dioxide emissions have been higher and lower in the early 2010s. The steady year-on-year decline occurred between 2013 and 2016. It is no coincidence that the second Obama cycle is the time when the most important (beyond communication) action on climate protection is expected to take place.

The Clean Power Plan was announced in 2014 and launched in 2015. The goal of the Plan was to reduce carbon emissions by 32 percent by 2030 compared to 2005 levels. Using 2005 as a base year is less ambitious than the 1990 figure most commonly used in the EU, because (unlike Hungary and most Western European countries) the US did not reduce its emissions between 1990 and 2005, but increased them significantly. However, given the growing US population, it is still a bold undertaking to target a reduction of more than 30 percent over a 25-year period. The target may even be met: at the start of the Plan, in 2015, US emissions were 13 percent lower than in the base year, and in 2005, by 2022, emissions had fallen by 18 percent below the base year. The administrations still have significant steps to take to reduce emissions over the remaining 6 years, but the goal does not appear unattainable.

The way the Clean Power Plan has been communicated to the US electorate says a lot about their perception of climate change. Of course, the health risks of climate change have been highlighted, but the focus has been on the financial quantification of how much (how many billions of dollars) weather extremes cost the country each year and how much US households can save on their bills thanks to the Plan. The fact that the Plan was conceived in the last years of the Obama administration shows when climate change really began to interest, alarm and frighten the masses. And the communication of the Plan illustrates exactly why people fear climate change. As principled as Obama's climate policy may have seemed, it has been very pragmatic about how to get people interested in fighting climate change.

Apart from the Clean Power Plan, the most visible climate policy effort of the second Obama administration was joining the Paris Climate Agreement. For Obama, this accession was primarily symbolic, as the goals the US would set and achieve as a member of the Convention would be the responsibility of subsequent presidencies. Yet it is not a trivial step, as the world's second largest emitter and largest economy has set its sights on combating climate change.

Source: Climate Policy Institute

Donald Trump

Unlike Obama, the latest Republican President of the United States is known as a climate denier, an enemy of the fight against climate change. He has earned this reputation in terms of his communication, with posts on social media denying global warming and frequent speeches criticising methods of curbing climate change, which he says are contrary to the country's economic interests. But he is most widely seen as a climate denier for having withdrawn his country from the Paris climate agreement during his presidency.

Trump has justified his departure by saying that the Paris Agreement, which he says is rotten to the core, protects polluters, punishes Americans and costs a fortune. He announced the withdrawal in the summer of 2017, but it is conditional on the country having been a member of the convention for at least three years, and then another year must pass before the withdrawal can take effect. Ironically, this meant that withdrawal could take place on 4 November 2020, the day after Joe Biden won the US presidential election. Given the importance of Biden joining the convention for reasons discussed later, Trump's withdrawal was effective for just over two months.

The posts and speeches below illustrate how critical the President was of climate change and, seemingly in contrast, how much he took the environment to heart.

Donald Trump's controversial comments on the environment and climate protection (BBC, 2020)

What is worth examining in relation to Trump is not whether his communication is a champion of climate and environmental protection, but whether his communication in the opposite direction was a political marketing ploy to win over the business-minded American public, or whether his actual climate and environmental policy was also destructive.

Looking at the most studied metric, carbon emissions, the four years of Trump's presidency have seen an increase from 2017 to 2018, a decrease from 2018 to 2019, and a decrease from 2019 to 2020 (the latter cannot be attributed to the president, as the closures have led to a decrease in emissions in most parts of the world). These increases and decreases (not counting 2020) were only around 3-3%, so we can conclude that under Trump's presidency, climate policy has neither reduced nor increased US emissions, so Trump is neither the climate champion nor the aggressive climate destroyer that his communications would lead us to expect. In his Affordable Clean Energy project, he has apparently prioritised energy affordability over sustainable production, but under his presidency he has also increased the share of renewables in the US energy mix. This dichotomy does not demonstrate either his indifference to sustainable energy production or that he has made great strides in the fight for clean energy, as both energy demand and renewable energy production have increased globally during this period. In terms of his climate and environmental policies, Donald Trump can be seen as an average US president.

Moreover, at the time of the 2020 elections, voters had a more urgent and pressing issue than climate change, which has long been a top priority. Trump's electoral defeat was probably neither due to his climate policy nor to his climate communication in the first place.

Joe Biden

President Biden on the day of his inauguration joined the Paris climate agreement, from which his predecessor had withdrawn from. This decision was significant: climate protection is not only important, it is the most important area, and Trump's withdrawal was not only a mistake, but his biggest mistake, because if climate protection was only one of the key tasks, and withdrawal was only one of President Trump's mistakes, he would have had the time to withdraw from the Convention later, not on the first day of the new administration. Beyond this symbolic measure, however, it is also worth looking at how the Biden administration's climate policy has evolved.

US carbon emissions increased in both 2021 and 2022 compared to the previous year, but both were lower than the 2017 and 2019 levels, which were almost neck-and-neck the lowest of the Trump cycle, if you exclude the first year of COVID. The increases in 2021 and 2022 can therefore be seen as more of a bounce-back from COVID than apathy from the Biden administration. It is a good indication of this that there has already been a decline in 2023. However, both the increases and the decreases (except for 2020) were small deviations from the final years of the Obama administration and the "peacetime" values of the Trump presidency. To fully assess the Biden cycle, we will have to wait until 2024, but it is already clear that of the last three US presidents, Barack Obama is the only one to have experienced a continuous decline in emissions for at least three years, with economic growth. This can be seen in the chart below.

However, as in the past, President Biden cannot be accused of inaction on climate and environmental policy. At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, the US joined more than 100 countries in joining an initiative to stop deforestation and start restoring forests. To achieve this, the Biden administration has set aside $9 billion for forest protection and restoration. A similar amount ($9.5 billion over a 5-year period) was earmarked for similar purposes under the Trump presidency as part of the Great American Outdoors Act. This shows how much deeper the communication gap between the two major US parties is than the real one.

Biden's biggest climate policy achievement is the detail of the complex funding package, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. This 2021 measure will allocate nearly a trillion dollars to fund a range of job-creating infrastructure investments, with hundreds of billions of dollars going to various sustainability improvements: expanding public transport and rail networks, improving electric vehicle infrastructure, water management and environmental protection. This kind of job-creating, economy-building approach to climate and environmental goals fits in with the American vision that has been present during the Obama and Trump presidencies: sustainability is only worth fighting for if it increases, or at least does not reduce, people's well-being - in political terms, it does not lose voters. But as with the last presidential election, it is doubtful that the 2024 election will be decided primarily on the climate policy of the last four years.

Source: Climate Policy Institute